A case study in the institutional archive

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Manager of Collections and Archives

November 30, 2023

Museums are sometimes thought of as warehouses for precious artworks and significant artifacts—with storage looking like the hangar at the end of Indiana Jones stuffed full of mysterious crates; however, a museum needs to provide much more than long-term object preservation. Museums also create exhibitions, educational programs, experiences, and engaging gathering places for visitors.

As a collections manager and archivist, I don’t mean to imply that storage is an unimportant part of a museum, only that, though museums do collect objects, museums also create assets, items, and records. From exhibition catalogs and touchable props, to memorandum and souvenir T-shirts, museums make a lot of stuff.

It might seem like a good idea to throw away museum-created items once they have outlived their usefulness (there is no such thing as unlimited storage space), but preserving selected quantities can create an important record of a museum’s actions. These records allow people to go back and examine the who, what, when, and why of an institution, both past and present.

Allow me to introduce to you the South Street Seaport Museum’s Institutional Archive by way of a case study. With over 750 linear feet of files, photographs, building plans, ephemera, and digital media, it would be a bit too much to describe each type of Seaport Museum-created record and how they are cared for. Instead, this case study of a 1970s outdoor exhibition titled Sidewalk History examines not only how the Institutional Archive was first organized, but how the Institutional Archive can also impact the care of the Seaport Museum’s permanent collection of artifacts and artworks.

Spotted in Storage

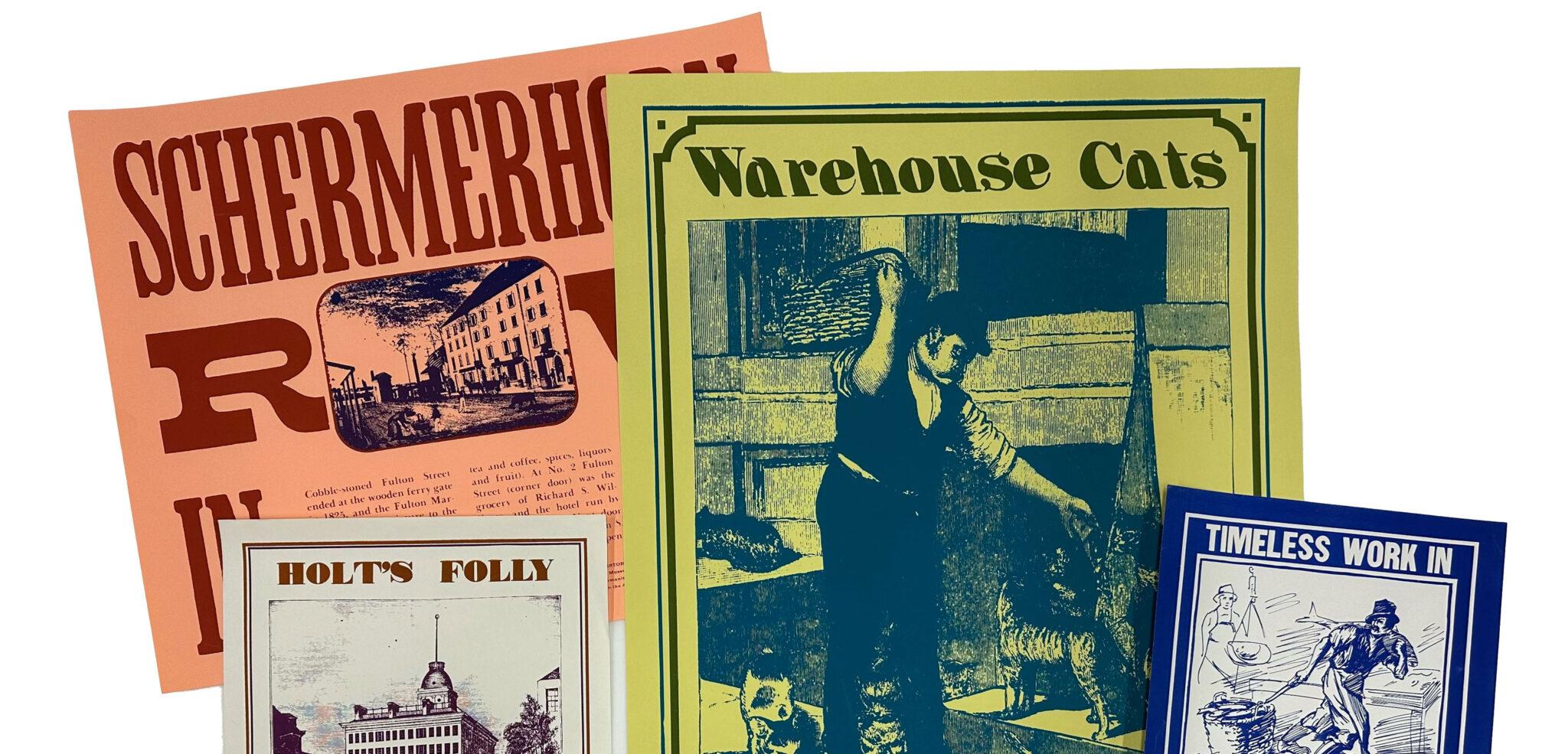

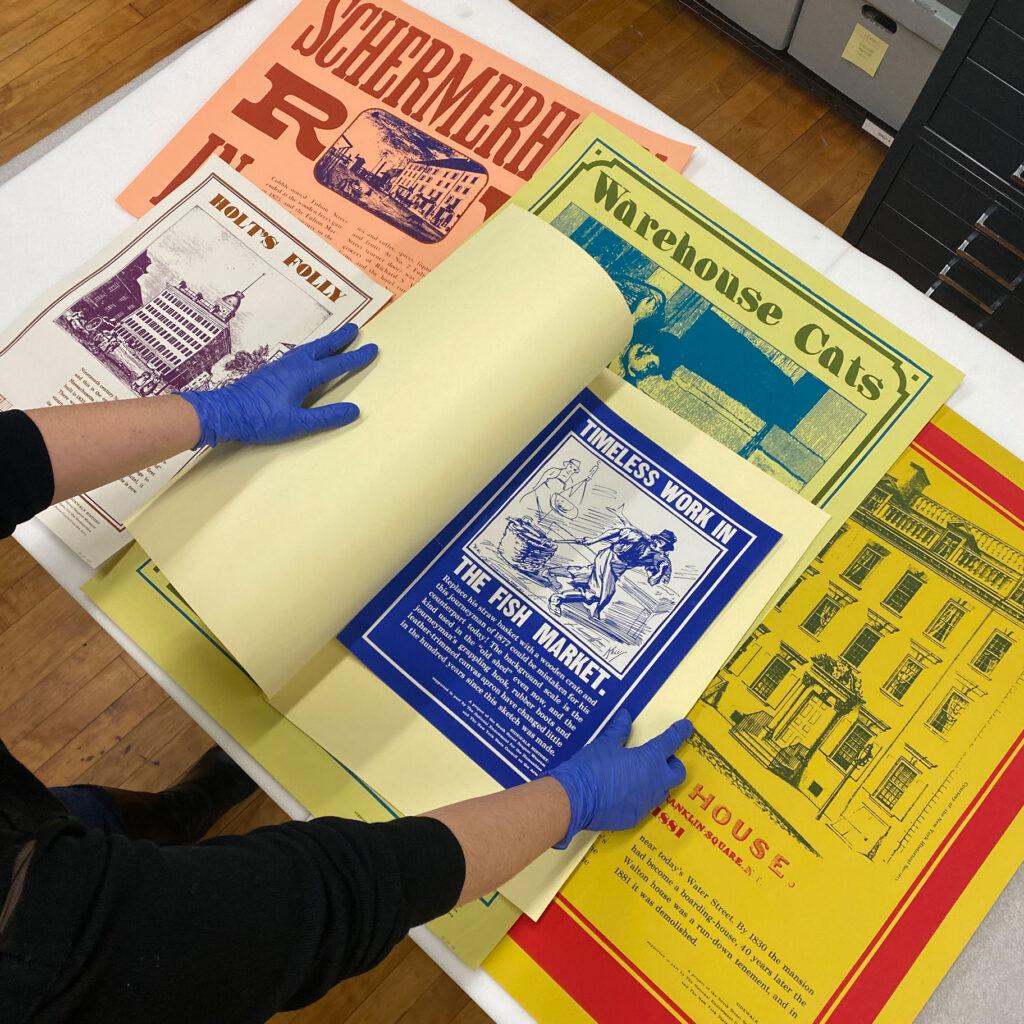

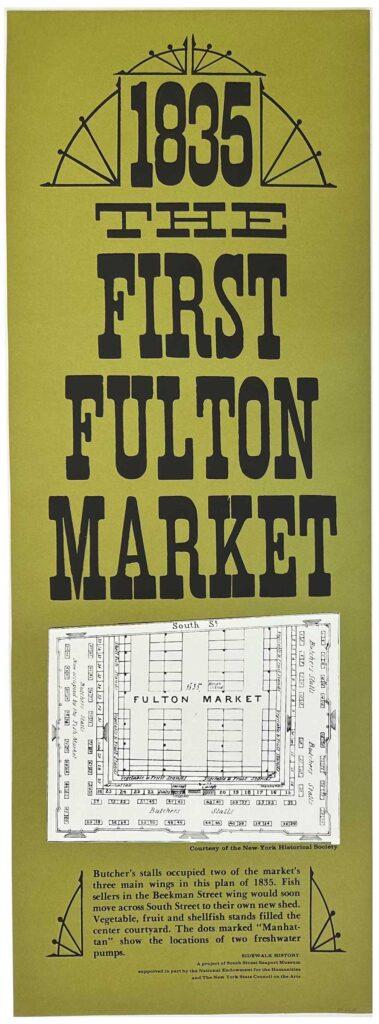

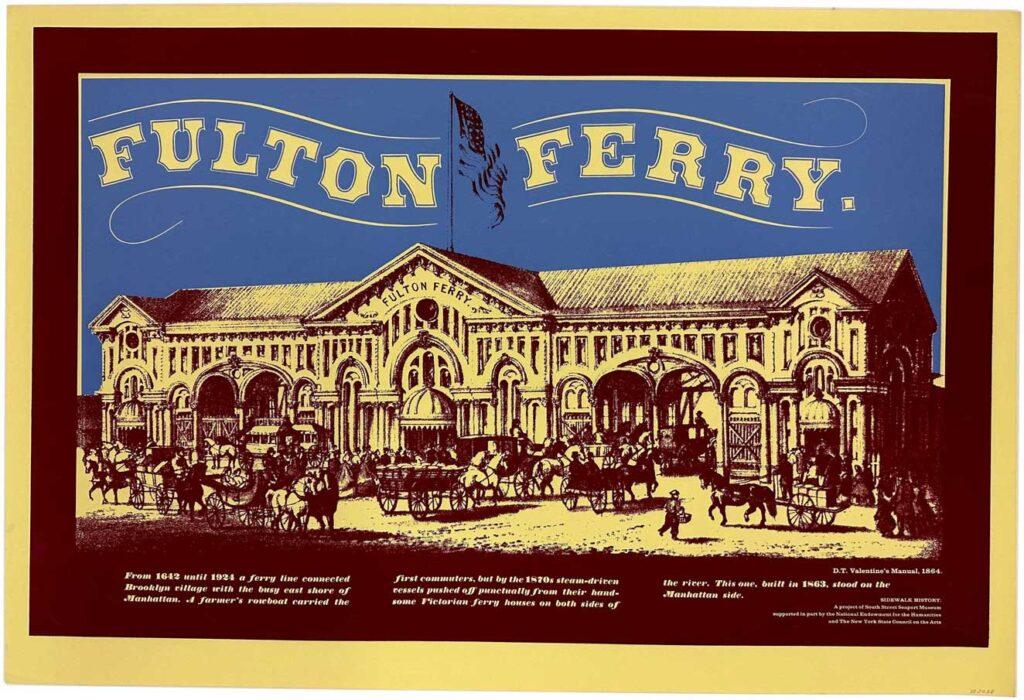

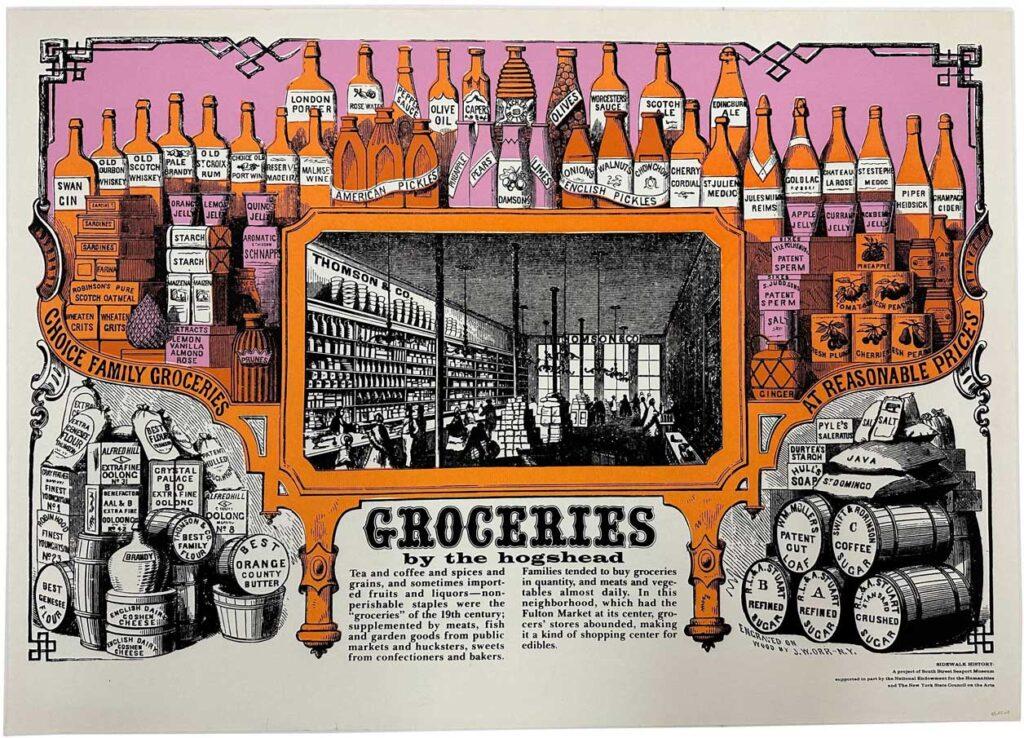

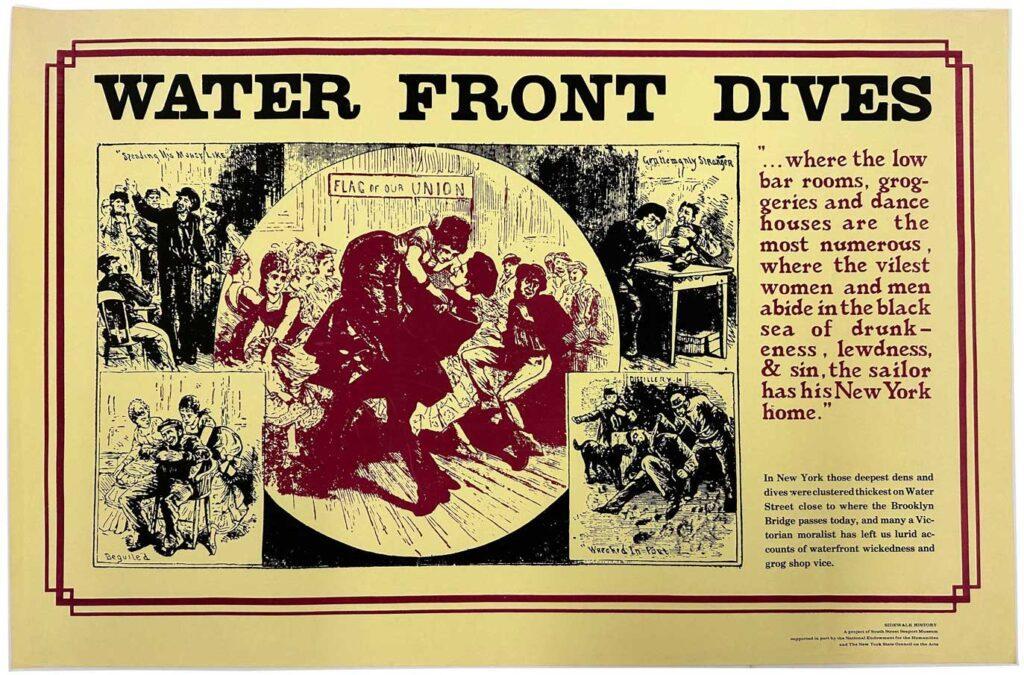

I first came across the words “Sidewalk History” during an inventory of the Seaport Museum’s storage cabinets for accessioned works on paper. These cabinets contain a variety of accessioned items, from 18th century maps and mid-20th century watercolor paintings, to illustrated newspaper engravings depicting New York City in the 19th century. In the midst of these expected artworks, I came across several folders of vibrantly-colored screen printed posters.

The posters have a small block of text reading “Sidewalk History: A Project of South Street Seaport Museum Supported in Part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and The New York State Council on the Arts.” This surprised me; I couldn’t understand why something made for a Seaport Museum project would be accessioned and stored with the permanent fine art collection!

To quickly explain what “accessioning into the collection” means, accessioning is both an action that documents how an object comes into a museum’s holdings, as well as a formal commitment of how that museum will care for the object. Once an object is accessioned into a museum’s collection, that museum commits to caring for it on behalf of the public in terms spelled out in their Collection Management Policy. Accessioning is one way of identifying which items that are meant to be preserved long-term for historical interpretation and research.

To give an example, if someone offered to donate an 18th century sailor’s diary to the South Street Seaport Museum, it would certainly be a candidate for accession into the collection. However, if someone proposed donating a high-end office scanner, it would be a generous offer to improve the Seaport Museum’s operations, but the scanner wouldn’t be something to accession into the collection.

Comparison of accessioned artifacts and Museum-made institutional archive material

I could tell the posters were accessioned since they were labeled with an accession number—the inventory number that allows museums to track individual objects and cross-reference their accession paperwork. To start my research into why these Museum-made posters had been accessioned, my first stop was pulling their accession, or formal acquisition, record.

Probing the Provenance

The accession files for the posters were pretty sparse. Ideally, an accession file includes a rationale of why an item was accessioned, describing its significance to a museum’s mission. There wasn’t a rationale in the file, but I understand why my predecessors may not have had the bandwidth to create a rationale at the time: the Sidewalk History posters were accessioned with over 300 other items!

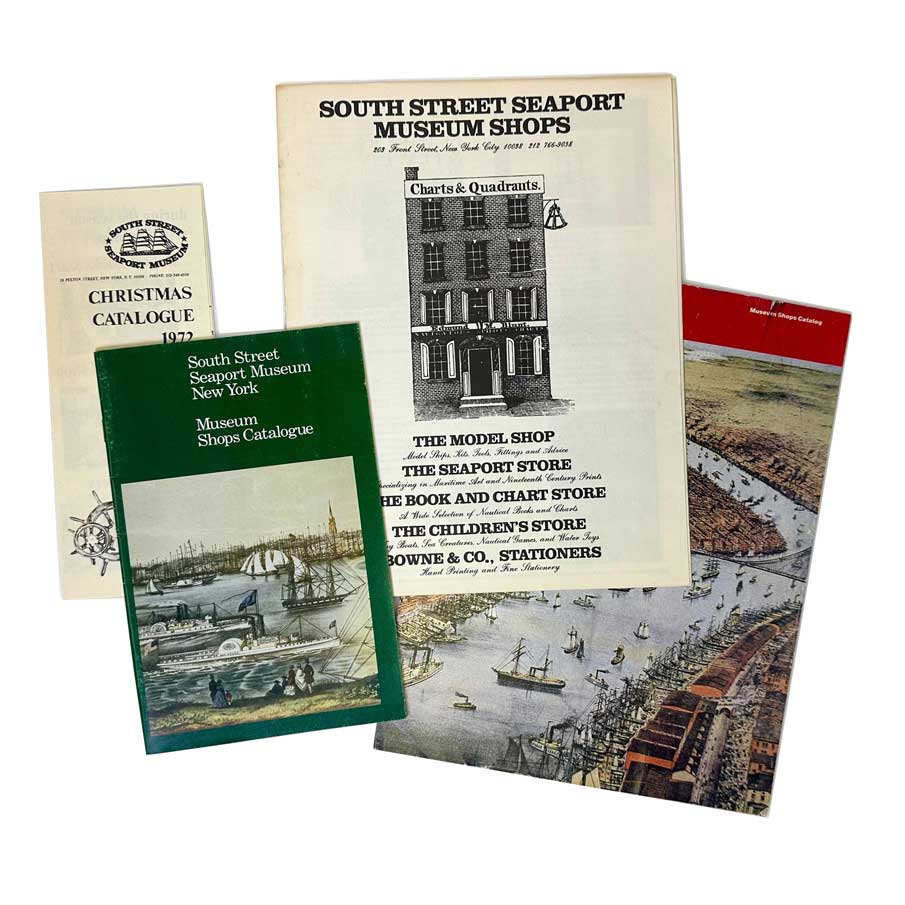

In 1985, the Seaport Museum took a closer look at the prints that were being sold in the Seaport Museum shop. 331 items were accessioned from the shop’s stock including reproductions of artworks, pages from 19th century atlases, and posters produced by other maritime collections. Perhaps the reproductions were accessioned as valuable reference material for researchers in the Seaport Museum’s collection (this was the time before Google Image search), but without more robust records, it’s not possible to know for sure.

Seaport Museum Store catalogs, ca. 1970s

Along with having nothing describing why the Sidewalk History posters were accessioned, the files had nothing about what the Sidewalk History exhibition even was. Only by looking into the institutional records produced by other Seaport Museum departments would I be able to learn who had created these posters and why.

Excavating Exhibitions

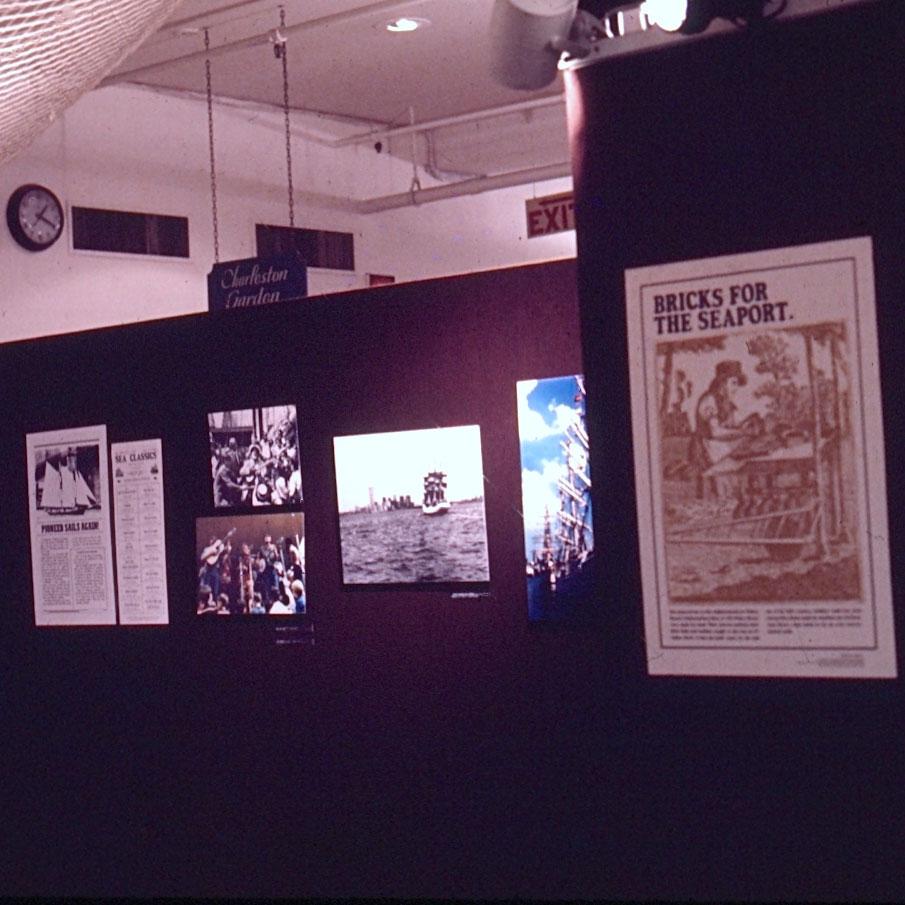

Since Sidewalk History was an exhibition, I started by looking into the Exhibition files. These records document past exhibitions put on by the Seaport Museum and include research and planning notes, object checklists, press releases, and photographs of the finished displays.

Information about past exhibitions can be critical for collections care. They describe how collections have been researched and interpreted, while photographs of galleries can help track an object’s past condition, display strategies, or location.

When museums share their institutional archives digitally, past exhibitions are often a priority. It makes sense; exhibitions explore objects and topics that the public finds engaging. Exhibitions are huge investments for museums in terms of money, time, and care, so having past exhibition content online is a great way to see continued public benefit from that work. And, like so many parts of a museum’s institutional archive, making exhibition records accessible helps communicate and contextualize how that museum’s identity and offerings evolved over time.

D. Talbot, photographer. [South Street Seaport Museum galleries], 1977. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

I found some early 1980s photographs of Seaport Museum galleries where I could spot one or two posters, but I didn’t find any other records of Sidewalk History in the Seaport Museum’s exhibition files. I think this is because the exhibition records focus on how collections artifacts are curated, interpreted, and displayed. Since Sidewalk History was an outdoor exhibition that didn’t take place in a gallery with collections objects, maybe its records weren’t kept with other exhibitions. I would have to look elsewhere to understand the creation of the posters.

Digging into Development

My next stop in the Seaport Museum’s Institutional Archives was the development department records. A museum’s development department is all about building relationships with people and institutions to support that museum’s operation and growth. Managing memberships, sponsorships, grants, and monetary donations are some of development’s key responsibilities. Since each of the Sidewalk History posters I found each had a credit line mentioning the National Endowment for the Humanities and the New York State Council of the Arts, I was hoping the Seaport Museum’s Development Department kept records of these partnerships…and I was right!

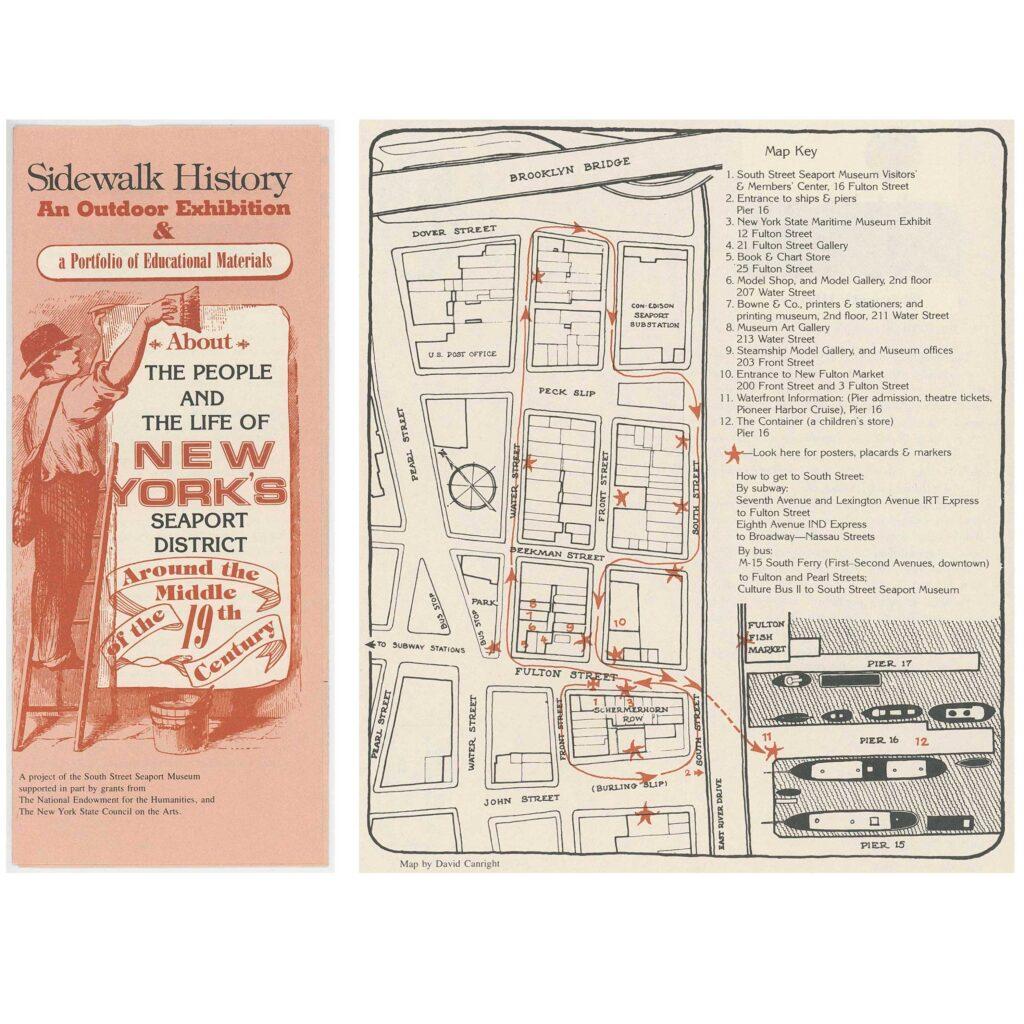

Example of one Development Department folder and Sidewalk History brochure

The files were a treasure trove of information on the Sidewalk History project. Since Sidewalk History was grant funded, the file included the Seaport Museum’s applications for those grants, financial records tracking the use of the funds, and regular reports on the project’s progress.

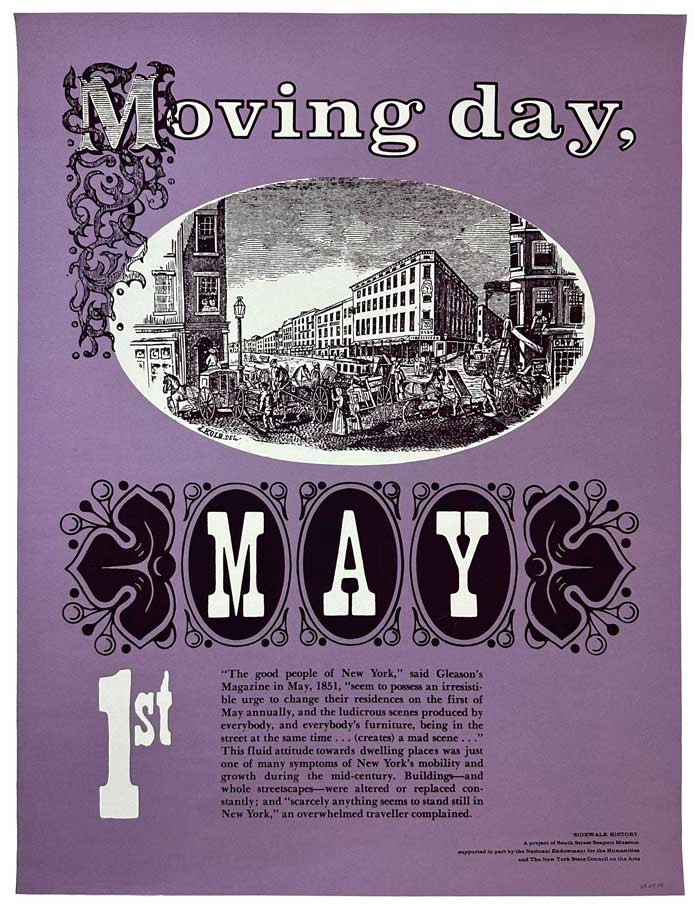

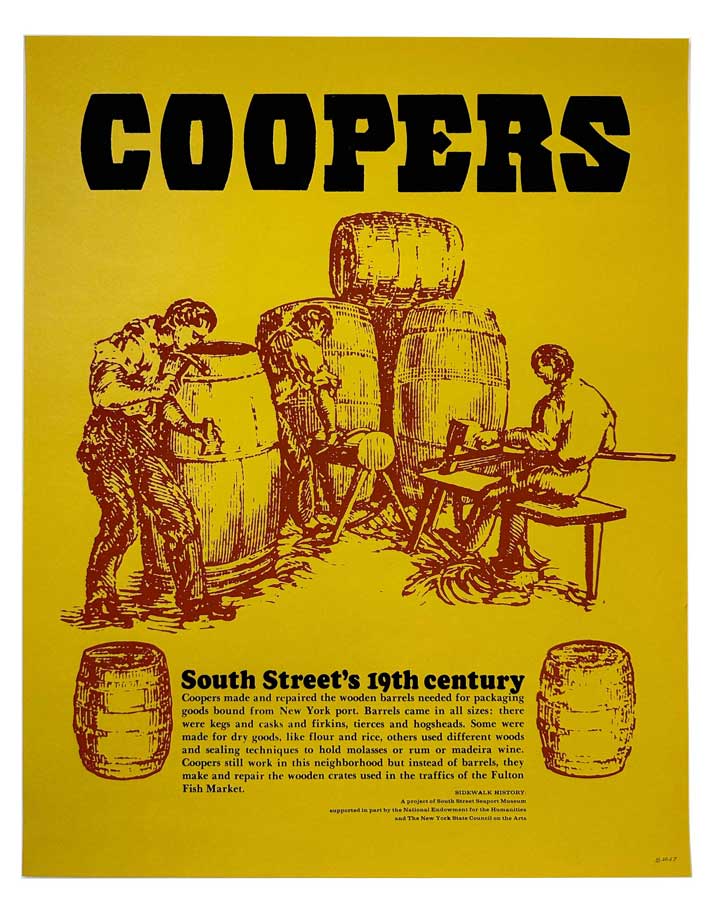

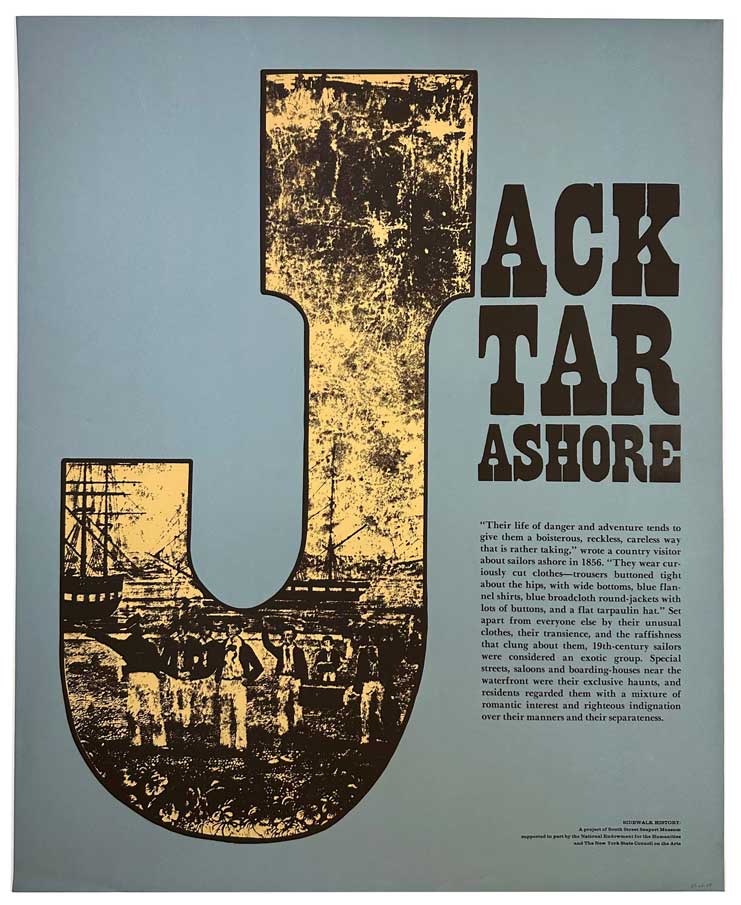

In these papers I learned the basic story of how Sidewalk History came to be; in early 1976 the Seaport Museum, like many other sites in the United States, was developing programs, events, and exhibitions to celebrate the United States Bicentennial. The grant applications for Sidewalk History describe the success the Seaport Museum was having with a recently published guidebook of the the South Street Seaport Historic District titled Walking Around South Street, as well as a gallery exhibition about specific Seaport residents from 1763–1783 titled Farewell to Old England: New York in Revolution. Sidewalk History was going to go even further by sharing more stories of life and commerce around South Street from 1815–1865, along with bringing more interpretation and insight for visitors exploring the streets of the historic neighborhood.

The grant writer describes it in better words: Sidewalk History would “…make the history and significance of the neighborhood available on the streets; a program directed to the majority of the visitors to the area who do not seek out books on local history, or even spend time in formal museum galleries. Our story, of the ordinary and the outstanding people whose individual enterprise and collective endeavor built here in the mid-19th century the commercial center of the New World can be told on the very sidewalks where it happened and on the brick walls of the actual buildings that housed it.”

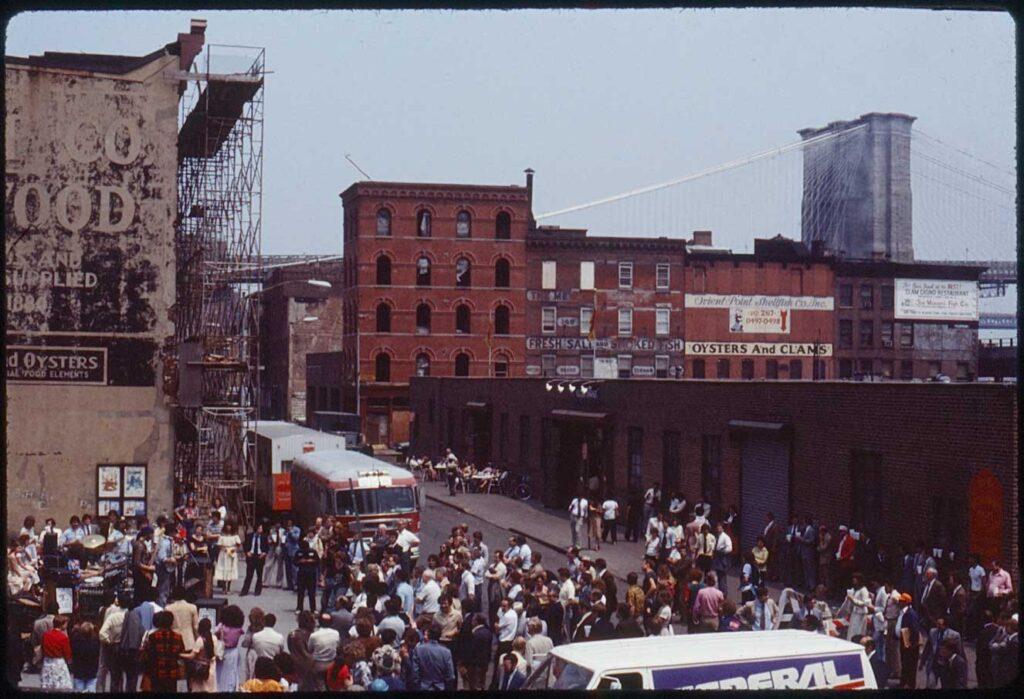

[View up Front Street during a summer concert], June 9, 1977. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Additionally, the Seaport Museum’s Development Department’s records included a brochure that mapped out a walking route to see all of the posters around the neighborhood. This brochure also pointed me to another part of the Institutional Archive, since it mentioned that Sidewalk History included an illustrated booklet to supplement the posters!

Perusing Publications

Locating the Sidewalk History booklet in the Institutional Archive was pretty easy. The Seaport Museum Publication Department files include records of how publications were created at the Museum, but it also includes multiple copies of each publication for long term retention.

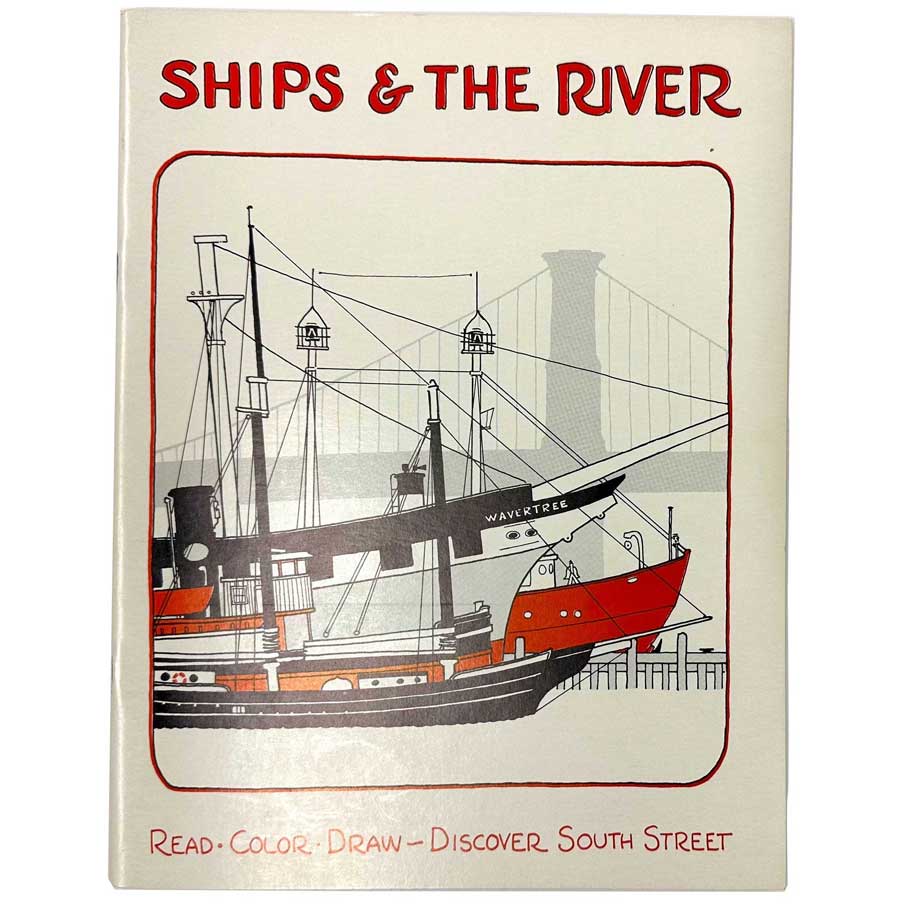

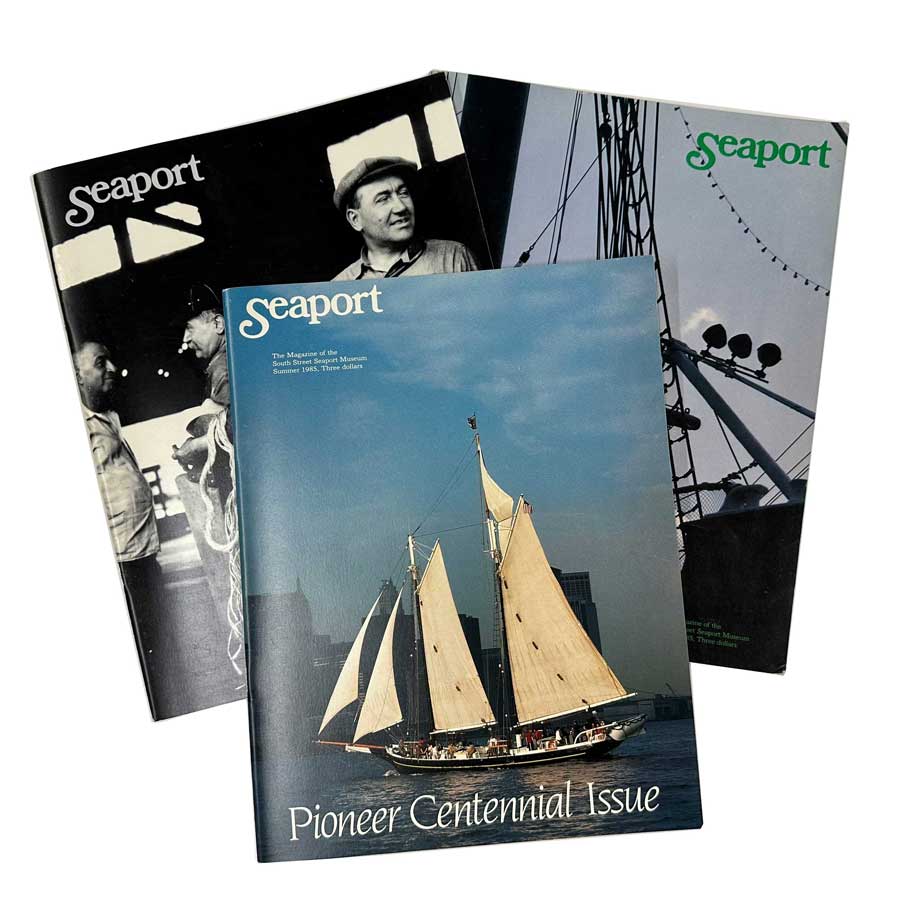

Seaport Museum publications include exhibition catalogs, newsletters, and books such as The Wavertree: An Ocean Wanderer and South Street Seaport Museum Cookbook. The Seaport Museum’s magazine South Street Reporter (retitled as Seaport in 1978) which ran from the Museum’s founding in 1967 to 2010, is the publication that I was the most familiar with when I looked into this part of the Institutional Archive; since the magazine covered Seaport Museum news as well as articles exploring the history of New York City and its waterways, the magazine could be as helpful as exhibition files for recording the status and interpretation of the collections.

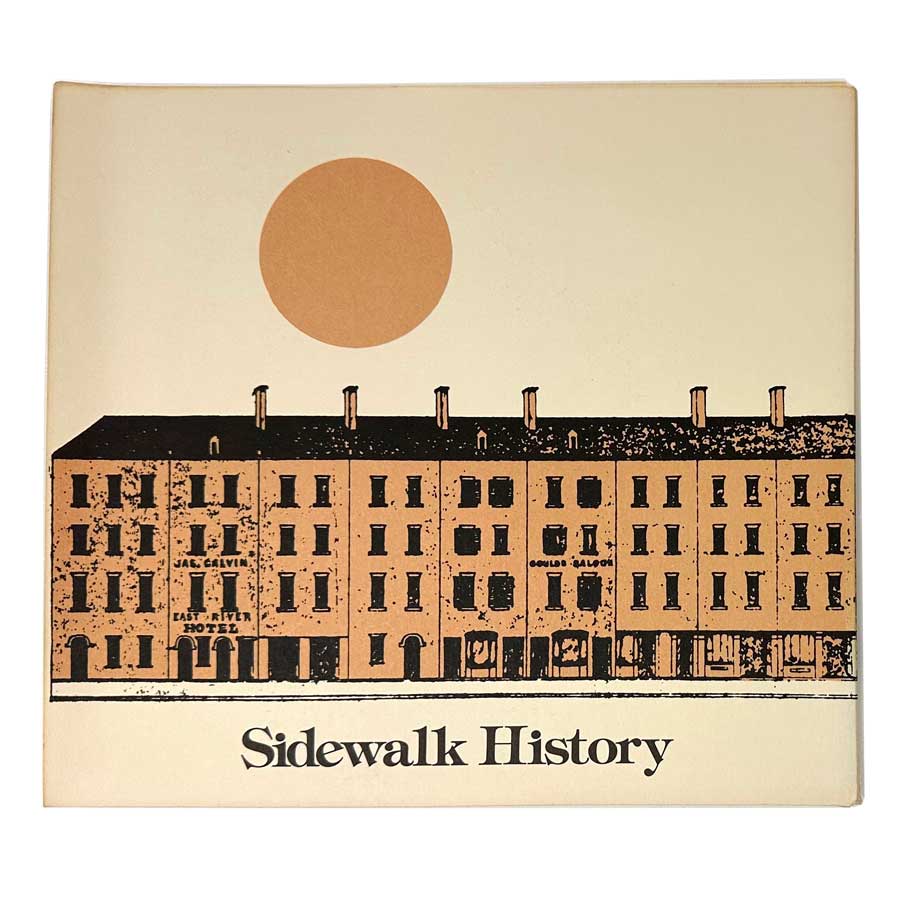

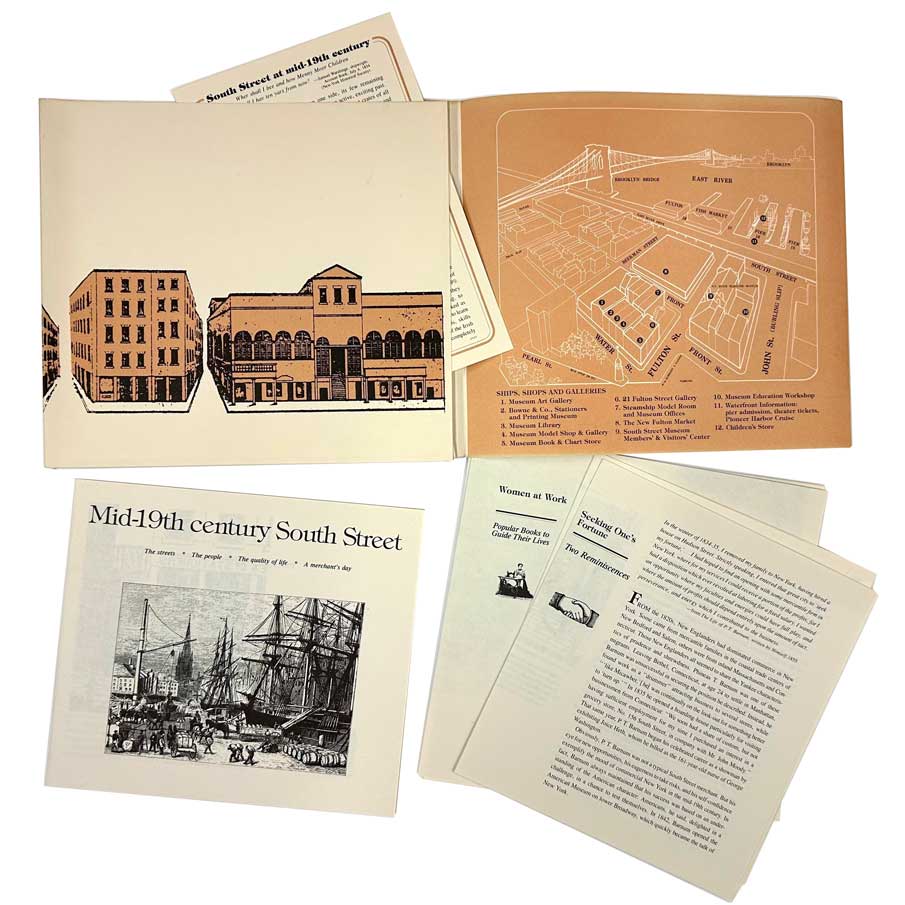

The Sidewalk History booklet is a tri-folded paper portfolio containing a booklet “Mid-19th Century South Street”, a paper card introducing the project, and four folded “broadsides” reproducing primary sources of the period. Since this exhibition publication was available for sale in the Seaport Musuem’s Shop and by mail order, it is possible some of you have a copy on your bookshelves!

Along with reuniting the Sidewalk History posters with its publication, I decided to check whether there was anything more about Sidewalk History to be found in the Museum’s publications. An article in the Winter 1976 issue of South Street Reporter introduced the outdoor exhibition to the public for the first time, and it was my first glimpse of the people who made Sidewalk History happen.

The article by Joanna Dean describes the work of several team members including project manager David Canwright, designer Roy Campbell, and historian Ellen Rosebrock, and how the project took shape. Rosebrock, who wrote much of the poster and booklet text (as well as the grant applications I mentioned earlier), researched collections across New York City to locate compelling illustrations and stories to bring 19th century South Street alive. She is quoted, “History is not recreated or reconstructed on South Street. It is already there, and our job is simply to make it visible and arresting. We think that the ‘posters’ purposely placed on the very spot where the thing they celebrate occurred, will have a special kind of attraction for people walking in the streets. Everyone who comes to South Street knows that history is there. They know that the old, grimy warehouses once were something they are not today- These posters will let them in on exciting (but invisible) facts about the past”.

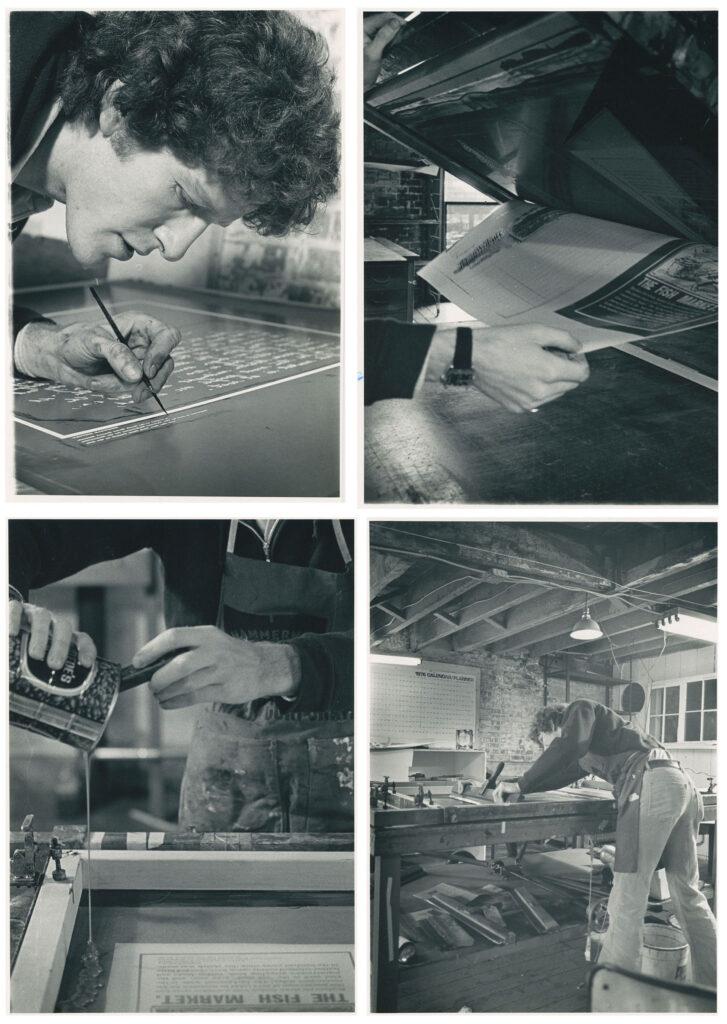

The use of posters, rather than formal engraved historical markers around the neighborhood, allowed for a greater range of vignettes and topics, like warehouse cats, cholera outbreaks, and oyster cellars. They were also a practical choice. Campbell stated in the article that “Posters seemed like an excellent idea because if they are stolen or marked up they’re not expensive to replace.” The magazine also included photographs of Campbell working in the silkscreen printing studio that the Museum set up for Sidewalk History on the second floor of 203 Front Street.

There were so many details about the creation of the posters in the Publication Department records (did you know the typefaces were selected from the types at Bowne & Co.?) that I felt I had found almost everything I needed to know about the Sidewalk History exhibition.

[Roy Campbell screen printing Sidewalk History posters], 1976. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

There was only one critical question left to answer: why were they accessioned into the permanent collection instead of deposited into the Institutional Archive in 1985? For my last stop in the Archive, I had to get meta and look at the records of the creation of the Institutional Archive itself.

Initiating the Institutional Archive

In the end, my research path took me back to the files of the Collections and Archives Departments. Among the memorandums and strategic plans was a hefty file containing a “Consultant’s Survey and Report”, written by project archivist Sally Brazil as part of a grant to assess the records of the Seaport Museum. Over 22 days in 1989, Brazil examined every place where Museum staff members stored critical records, and interviewed the staff on the history of the institution and their departments.

Though the report described over 500 linear feet of unmanaged records stored in places across the neighborhood, Brazil wrote that the effort of forming an Institutional Archive would be well worth it:

“Wonderful, valuable institutional records exist at the South Street Seaport. Original correspondence and project files of past residents and key personnel tell the always complex history of the Seaport from its early, volunteer-driven days to today’s dizzying mix of not-for-profit and commercial working relationships.

The restoration of each of the Seaport’s buildings and ships, the public records of the Seaport’s relationships to the people and government of New York, the intricacies of forging a partnership with Rouse and Company, a chronology of exhibits and Seaport sponsored-events, and ship restoration projects can all be reconstructed…”

The 1989 Survey and Report must have been convincing, since the Seaport Museum organized the Institutional Archive later that year based on its recommendations. From that point on, new “old” records were regularly added to the Archive based on their long-term value. Though the level of care allocated to the Institutional Archive records has waxed and waned in the decades since 1989, the guidelines from Brazil’s Report were referenced again in an in-depth assessment done again in 2012, proving that the foundational work to organize the records remains key to its management. As a side note, the 2012 survey included creating box and (partial) file lists, which was instrumental to finding the Sidewalk History-related files in the Development and Publications records.

So why were the Sidewalk History posters accessioned into the art collection in 1985, instead of deposited in the Seaport Museum Institutional Archive? It is because there was no Institutional Archive until 1989!

The staff in 1985 likely recognized that the Sidewalk History posters should be saved by the Seaport Museum as a tangible record of its 1977 exhibition—that there was value in preserving the Museum’s memory. Without an Institutional Archive, the best method for tracking and caring for the posters was accessioning, even though they were Museum-made. It reminds me of the saying “when all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.”

The decision to accession in 1985 likely saved the most critical part of the Sidewalk History exhibition from eventually being lost; with the records from the Institutional Archive I now know that there were 50 distinct posters designed for Sidewalk History, but today only the 36 examples accessioned in 1985 remain.

Takeaways

I hope this case study into the origin and mysterious accession of the Sidewalk History posters illustrated just how important caring for a museum’s records can be. The Seaport Museum’s Institutional Archive is an unparalleled resource for continuing to care for the Museum’s collection, buildings, and historic fleet.

[Speaking of the fleet, I had considered focusing this entire blog post on the records of the Waterfront Department, which includes the ships’ plans and technical drawings, photographs, and documents how the Museum’s historic ships came to South Street, as well as how they have been restored and maintained over decades. It is actually the part of the Museum’s Institutional Archive that is used most regularly by staff and researchers!]

To close off the story of the posters, they’ve been deaccessioned from the permanent art collection and are now stored with other oversize Museum exhibition posters as part of the Institutional Archive.

There is also now an entry for Sidewalk History in the Exhibition Department record’s list of Museum exhibitions that will point potential researchers to related materials in other sections of the Institutional Archive.

On a personal note, what I enjoyed most about researching in the Museum’s Institutional Archives was learning about how this one exhibition came to be, and the thoughtfulness and hard work of the people at the South Street Seaport Museum at that time. I’m sure there are many contributors to Sidewalk History that I still do not knowIt was a great reminder that there has been a long line of passionate people who care for South Street.

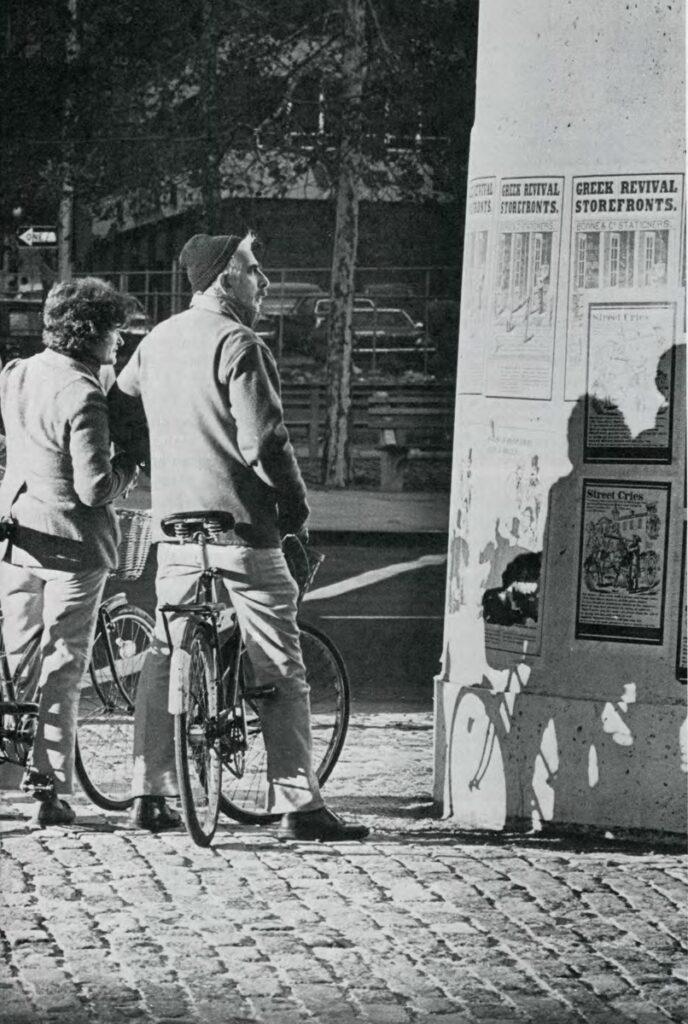

Anthony Dean, photographer. [Cyclists stopping to view Sidewalk History posters], 1977. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Lastly, if you wish you could have seen Sidewalk History in 1977, I highly suggest checking out the Seaport Museum’s current partnership with Urban Archive—an app that maps archival images from dozens of collections to New York’s streets to existing locations. There is still so much to see and discover about our shared histories when walking through the South Street Seaport Historic District.

Additional Readings and Resources

“Museum Archives Guidelines”, Society of American Archivists. Revised February 2022.

“Mellon Grant Helps Exhibition Archive Go Online” Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, September 22, 2023.

“Collections Management Policy”, South Street Seaport Museum. Revised and adopted by the Board of Trustees, May 1, 2019.

“The Sidewalk History Project” by Joanna Dean, South Street Reporter Volume X No.4. Winter 1976-1977.

Sidewalk History, South Street Seaport Museum, New York. 1977